The Pentagon Wants to Spend $141 Billion on a Doomsday Machine

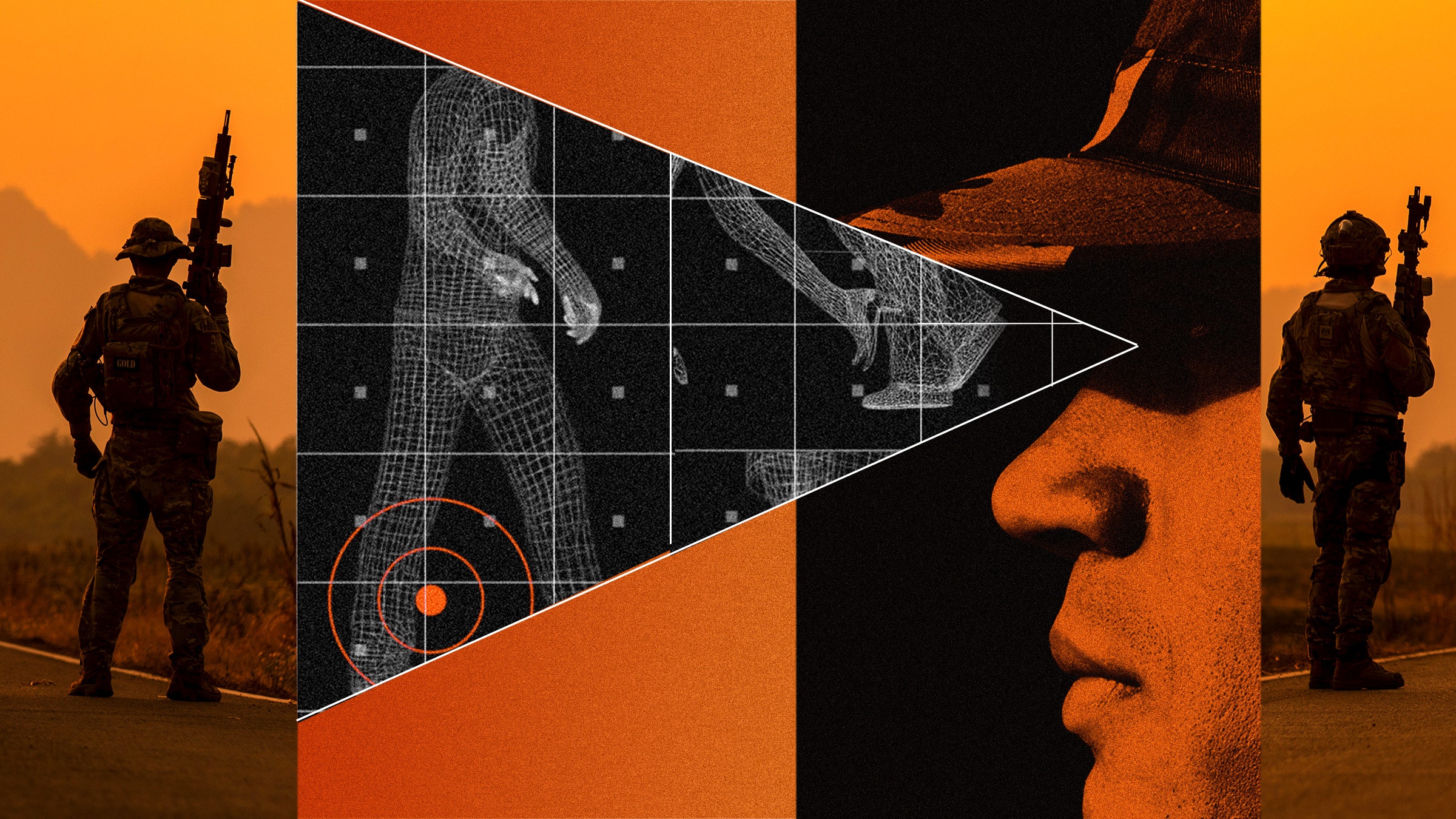

If you’re one of the millions of Americans who live within range of its 450 intercontinental ballistic missile silos, the Pentagon has written you off as an acceptable casualty. The silos are scattered across North Dakota, Montana, Colorado, Wyoming, and Nebraska in a zone of sacrifice—what lawmakers and military planners have long called the “nuclear sponge.”

Despite real concerns over cost overruns, human lives, and the general uselessness of ICBMs, the Pentagon is barreling forward with a plan to modernize those silos and their missiles. Right now the Department of Defense thinks it’ll cost $141 billion. Independent research puts the number at closer to $315 billion.

All of that is money the Pentagon plans to use to build a doomsday machine—a weapon that, were it ever used, would mean the end of human civilization. Such a weapon, most experts agree, is pointless.

ICBMs are a relic of the Cold War. The conventional thinking is that a nuclear power needs three options for deploying nuclear weapons—air-based strategic bombers, sea-based stealth submarines, and land-based missiles. That’s the nuclear triad. Should one leg of the triad fail, one of the other two will prevail.

First deployed throughout the 1960s, America’s ICBMs are old. According to the US Air Force, the Minuteman III missiles need to be decommissioned and replaced with a new missile called the Sentinel. Northrop Grumman has a plan to do it. The Air Force wants to buy 634 Sentinel missiles and modernize 400 silos and 600 other additional facilities.

This would cost probably hundreds of billions of dollars. The prices have spiraled so out of control—up 81 percent from 2020 projections—that it triggered a little-known congressional rule aimed at curtailing costs. If a weapons program’s costs bloat beyond 25 percent of their original projection, the DOD has to justify the need for the program and the rising costs. On July 8, the Pentagon released the results of the review. Unsurprisingly, it said it needs the weapons. A congressional hearing is scheduled for July 24.

There’s been a lot of congressional back and forth about the program. Representative Adam Smith, a Washington Democrat and ranking member of the House Armed Services Committee, has been public in his opposition to the program. Senator Deb Fischer, a Nebraska Republican, has said that people calling for cuts to the nuclear program are living in a dream world.

“Land-based ICBMs, by virtue of their location in our heartland, are also unlikely to be targeted by enemy attack,” Fischer said in a recent Newsweek op-ed.

“Military planners would be surprised to hear that,” says Joseph Cirincione, retired president of the Ploughshares fund and former director of nonproliferation at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “Because a major justification for the program is that it would do exactly that, it would force the adversary to target these warheads … they’re counting on the adversary thinking about it.”

At one point in his career, Cirincione was a congressional staffer who worked on military reform for almost a decade. “When I was on the Armed Services Committee staff in the ’80s and ’90s, I heard about the sponge,” he says. “It’s one of the two chief justifications for the ICBM.”

The other is its responsiveness—the idea that it can fire and hit its targets a few minutes faster than a submarine or a bomber. “The arguments get very vague, and they’re intentionally kept vague,” he says. “And you hear that people sort of make this profound-sounding strategic rationale—value-laden phrases like, ‘They’re the backbone of our national defense strategy backbone.’ But probing that, digging under it, you realize it’s just built on sand. There’s no foundational logic to this beyond Cold War targeting calculations.”

The targeting calculations are absurd and frightening. These silos exist so that the United States can launch an all-out nuclear attack on Russia or China. The goal of the strike would be the total destruction of the population centers of the opposing nation. It would not be about an in-kind attack, but rather the total obliteration of the enemy. This is precisely why many experts consider them useless.

“If we used the ICBMs it would be the end of human civilization, even without an adversary hitting the United States with a single warhead,” Cirincione says.

“I think there’s no point to the ICBM silos,” says Tara Drozdenko, director of global security at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “Our submarine-based missiles are quite accurate. They’re basically impossible to find, and so they don’t have the vulnerability as our fixed-in-one-spot silos have.”

This means that, in practice, the point of the ICBMs is to draw enemy warheads away from population centers and toward more sparsely-populated areas of the US. But those warheads hitting the United States would have profound consequences for the planet and its people. A study from Sébastien Philippe at Princeton’s Program on Science and Global Security found that an all-out attack on the nuclear sponge would lead to the deaths of millions of people in the US, Canada, and Mexico.

“It’s not just absorbing a nuclear attack,” Philippe tells WIRED. “It’s like when you pour water on the sponge, and then you press onto it, it’s going to spill everywhere. So spill-out from that sponge is massive radioactive fallout across the country.”

In Philippe’s study, he and a team used recent weather data to model how radioactive fallout would flow across the planet after an attack on the nuclear sponge. “Overall, almost 300 million were at risk of receiving lethal doses depending on where the wind would blow…just from having that weapon system attack,” he says.

The fallout would be severe. “We’re not talking about having cancer in 15, 20, 30 years. We’re talking about your cells and organs and your body shutting down in days, weeks, or months after the explosion.”

The consequences of the Sentinel program extend beyond a worst-case scenario, however. The Air Force’s plan proposes a monumental feat of engineering. To support the new missiles, the Air Force plans to demolish 45 missile alert facilities and build at least 24 new ones in their place. It will renovate the existing 450 silos, construct 3,100 miles of utility corridors, and raise 62 300-foot-tall communications towers. The Air Force says it can do all this by 2036.

That’ll take a lot of labor power—roughly 3,000 temporary workers. They’ll have to live somewhere, and current Sentinel plans involve the construction of temporary housing for the folks who come to work on the silos. “That’s something the communities are worried about,” Philippe says.

Communities in silo states like North Dakota lived through something similar during the fracking booms of the past two decades. Massive shale deposits moved temporary workers across western and midwestern states. Crime followed. Opposition to the project on tribal lands and local communities is already building.

Kimball, Nebraska, will be the site of one of these early pioneer camps. The pioneer camp will construct “The Hub,” a three-story dormitory filled with 600-square-foot apartments. It’ll be wildcat hours, with Hub workers living onsite for a month at a time and pulling 10-hour shifts before returning back home to family. The construction of this facility will double the population of Kimball while it’s in use.

Perhaps the most ludicrous part of the Sentinel program is that the US doesn’t need ICBMs at all. Its sea-based stealth submarines are hard to detect and harder to destroy. If an enemy ever threatened a nuclear attack on America, a submarine would be available to retaliate. In addition, the US has stealth bombers that can deliver nuclear weapons from the air.

So why drill holes in the ground and fill them with nuclear weapons? In her op-ed, Fischer gave away the game: It’s about fear. “We invest in nuclear weapons because they underwrite every operation or negotiation undertaken by our nation,” she wrote. “Effective diplomacy—especially with other nuclear powers—means nothing if it isn’t buttressed by a formidable nuclear deterrent.”

Fischer doesn’t speak for everyone at the Pentagon nor every politician on the Hill, but she does highlight a dangerous strain of thinking. In order for America to be a major player on the world stage, the logic goes, the world has to believe it’s willing to destroy the world if it doesn’t get what it wants.