The Hugely Important Ocean Current You’ve Never Heard Of

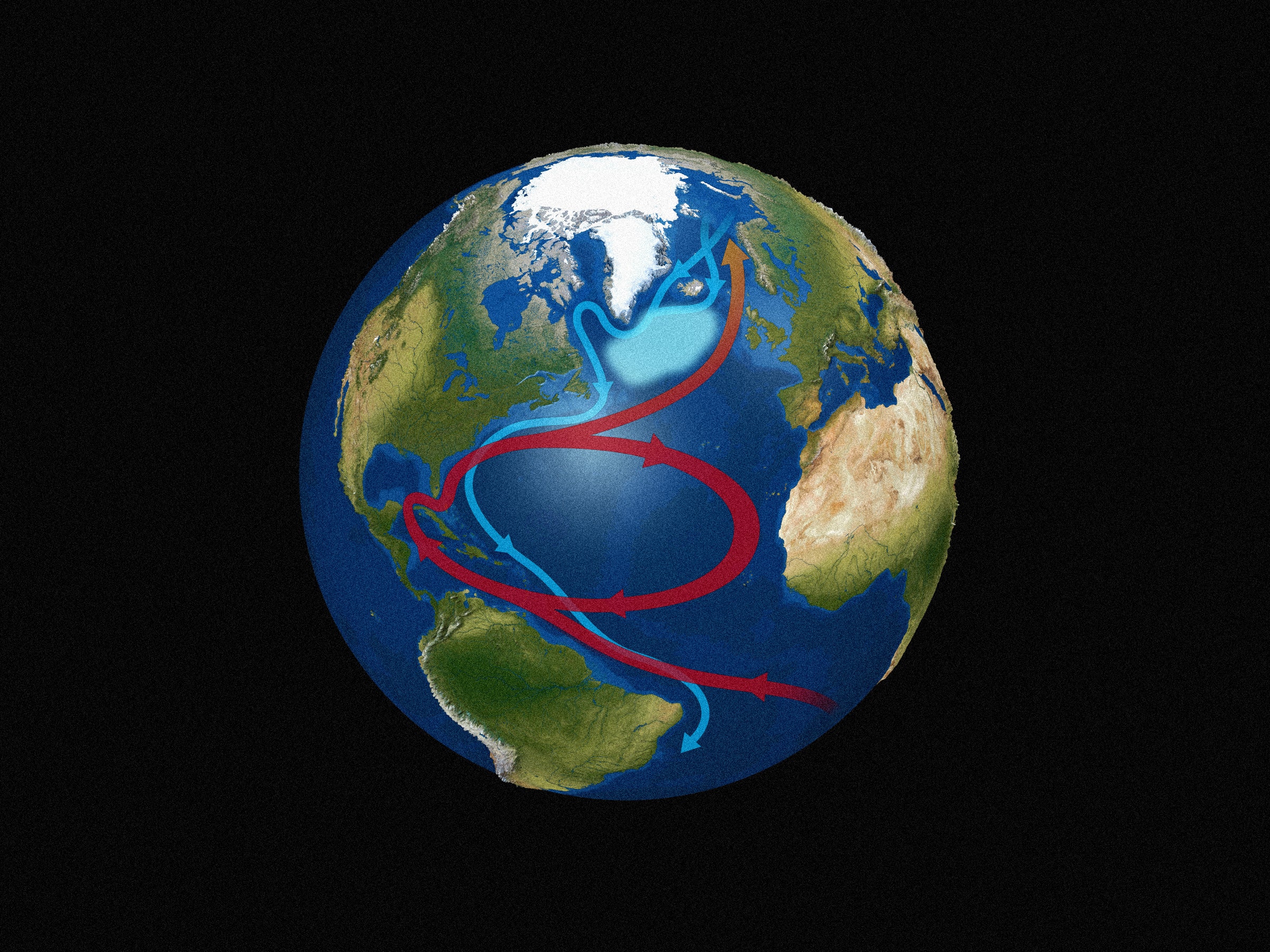

If you haven’t heard of it before, you’re about to become intimately familiar with the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. This system of currents—which brings water up the Atlantic from the southern tip of South America, through the tropics, and all the way to the coast of Iceland before looping back down south—plays a key role in keeping our planet’s climate stable. It keeps northern European winters relatively mild, provides nutrients to ocean life, and brings much-needed rain to agricultural systems in equatorial zones.

Researchers who study the AMOC say this system is showing signs of instability, and it could shut down entirely—and soon. If the current slows down or stops, it would potentially kick off an ecological disaster of epic proportions. Deep cold spells, crushed food systems, entire regions in drought.

This week, we bring WIRED features editor Sandra Upson onto the show to talk about the AMOC, the research that’s being done on it, and what life would be like on Earth if the current reaches its tipping point. Buckle up.

Show Notes

Read “How Soon Will the Atlantic Ocean Break? Two Sibling Scientists Found an Answer—and Shook the World,” Sandra Upson’s WIRED feature on the researchers who are studying the AMOC and who have estimated the current could collapse in the next 30 years or so. Read our previous coverage of the AMOC research that kicked off the present debate about when it could reach the tipping point.

Recommendations

Sandra recommends watching trashy reality shows in a language you’re trying to learn as an informal and entertaining study aid. Mike recommends embracing Brat Summer—IYKYK. Lauren recommends the book The Wave by Susan Casey, which is about the science and joy and terror of big waves.

Sandra Upson can be found on social media @sandraupson. Lauren Goode is @LaurenGoode. Michael Calore is @snackfight. Bling the main hotline at @GadgetLab. The show is produced by Boone Ashworth (@booneashworth). Our theme music is by Solar Keys.

How to Listen

You can always listen to this week’s podcast through the audio player on this page, but if you want to subscribe for free to get every episode, here’s how:

If you’re on an iPhone or iPad, open the app called Podcasts, or just tap this link. You can also download an app like Overcast or Pocket Casts, and search for Gadget Lab. We’re on Spotify too. And in case you really need it, here’s the RSS feed.

Transcript

Note: This is an automated transcript, which may contain errors.

Lauren Goode: Mike.

Michael Calore: Lauren.

Lauren Goode: How often do Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation currents keep you up at night?

Michael Calore: I’m sorry, what?

Lauren Goode: AMOC currents.

Michael Calore: No, I don’t. It sounds like a climate change doomsday kind of thing.

Lauren Goode: Unfortunately it is. We’re about to get real nerdy about this one.

Michael Calore: I can’t wait. Let’s do it.

Lauren Goode: Let’s do it.

[Gadget Lab intro theme music plays]

Lauren Goode: Hi, everyone. Welcome to Gadget Lab. I’m Lauren Goode. I’m a senior writer at WIRED.

Michael Calore: And I’m Michael Calore. I’m WIRED’s director of consumer tech and culture.

Lauren Goode: And we’re joined this week by WIRED features editor Sandra Upson. Sandra.

Sandra Upson: Hi. Hi, hi.

Lauren Goode: It’s really great to have you on the Gadget Lab. Hi.

Sandra Upson: Hi.

Lauren Goode: Sandra has been my features editor before. Sandra, have we podcasted together before?

Sandra Upson: Never ever.

Lauren Goode: All right. First time for everything. Let’s start a new trend right now, but today we asked you to come on the show because you have an incredible new feature story out in WIRED about this current that I mentioned in the intro, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation Current. Yes, I’m reading that from a script. And if people haven’t heard about this before, they will now because this current, which flows across the entire Atlantic, gives us yet another glimpse into what potential climate disaster could look like. The current has been slowing, and while we’re not at this point yet, a total shutdown of the current could trigger, Sandra, you wrote this, a profound global scale reorganization in Earth’s climate systems.

We’re talking about deep cold spells, crushed food systems, entire regions in drought. It quite literally could be disastrous. So everyone should buckle up for this podcast episode and stick with us because you’re about to learn more about currents than maybe you ever wanted to, and for good reason. First, Sandra, I have to know, I love asking our feature writers this. What actually led you to this story?

Sandra Upson: I was led pretty directly by our former editor in chief, who at one point said, “We should really write a story about what happens if the AMOC collapses.” So this was now maybe two years ago, and at that time, the AMOC was sort of percolating through the news cycle, just kind of doom and gloomy like, “Things are looking a little weird in the Atlantic. Something is not so great. This might actually become disastrous. Maybe this current system will actually stop one day.” Should we be very worried, a little worried, lots worried? That kind of tone.

And so he had read this famous New Yorker article by Catherine Schultz many years ago that was like, “What happens if the Seattle earthquake actually happens?” And she very beautifully stepped through the whole chain of events that would follow. And so his vision was the chain of events that follow is a collapse of the AMOC. It took about one phone call to realize that that was never going to happen. It’s just way too complex, way too tied into every other climate system. You cannot make prognostications like that. It’s just really uncertain. There’s not enough data to draw a clean picture.

So I wasn’t sure what to do at that point. I called a bunch of writers, said, “Hey, what do you think? You want to write about the AMOC? One guy said, I already wrote about the AMOC.” Another woman said, “Yeah, never. Not touching that.” Another one was like, “Yeah, I’m just going to get so much hate mail. I can see it all writing itself. So no thanks.” So that went nowhere. Finally, last July, August, this paper came out, the one that I ended up writing the story, and it got so much press, just tons of headlines.

Everyone was talking about how they had figured out that the AMOC was going to collapse really soon, which isn’t exactly accurate, but that’s how it was often portrayed. So that just started to make it feel more urgent that, “Well, it’s really something that’s in the global consciousness now. What does it mean?” Do we really think it’s going to collapse soon? So that was the moment when we started to look at it again as a team. And what kicked it off for real was honestly the fact that it was sibling scientists that there was just this extra human dimension to it that it’s going to have a little humanity to it, built in.

So that felt like enough of a starting point to go down this road. Beyond that though, I had no idea how I was going to make it work, but it was like, “OK. Let’s go visit the Danes. We’ll start there.”

Michael Calore: I’m sure one of the challenges of making it work is making people aware of what the AMOC is and how important it is. So maybe you could do a little bit of that work for us now and do your best to describe what this current is and what it does in the Atlantic.

Sandra Upson: Sure, sure. Sounds easy, doesn’t it? Yeah.

Lauren Goode: So it’s a lot of water.

Sandra Upson: It’s a lot, so much water. It crosses the two meridians. So Atlantic, it’s in the Atlantic. Meridional, it crosses the hemispheres, so it’s both in the Northern Hemisphere and the Southern Hemisphere. Overturning means it is on the surface at one point and then it sinks and goes to the bottom. So there’s this literal overturning of the current where it goes down, changes direction and goes along the bottom of the ocean down to Antarctica.

So it has this funny little figure eight pattern, but half of one arm of the current, you could say, is at the surface and the other arm is at the bottom of the ocean. It transports a lot of nutrients. It transports carbon. It just brings stuff from the surface down to the depths of the ocean. It also connects to obviously the atmosphere. So it’s related to surface winds. The AMOC connects to the Pacific circulation system and basically is connected to all other oceans in the world.

But you can isolate the Atlantic part as this big loop that goes from along the coast of South America to North America, across to Greenland and Iceland. That’s where it overturns, goes down, and then crawls along the bottom of the ocean to Antarctica.

Lauren Goode: And you also referenced in your story something called the warming hole, which I wanted to ask you about that because of all the spots on the globe that are starting to show evidence of temperatures rising due to climate change, this current seems to have been somewhat immune from that.

Sandra Upson: So what I didn’t mention in my long-winded explanation of what the current looks like is that it brings heat from the tropics. So that point where it’s leaving South America and it’s near the equator, it carries … The surface water heats up from all the incoming solar radiation, and it brings that warm water to the north to Iceland and Greenland, and that’s where it releases when it meets cold water. And that warmth warms up Europe. That’s the basic idea and that’s how it became known as this warming engine for Europe. The warming hole is a little different. That is basically a sign that the AMOC is not bringing as much heat as it used to.

Lauren Goode: Got it.

Sandra Upson: So it should be warmer than it is. So the hole means it’s less warmth. It used to be called the cold blob, and then it got rebranded as the warming hole, but it should be warmer if everything was working well. And the fact that it’s not suggests that something is broken.

Lauren Goode: Got it. OK.

Michael Calore: So you’ve mentioned that scientists have noticed that the AMOC is slowing down and could stop. How do they know this? Why are they hypothesizing this?

Sandra Upson: So there’s some data that is showing that the actual overturning, the part where surface water falls to the bottom of the ocean, is slowing down. So there are some measurements suggesting that. The problem is that those measurements are pretty … They’re not a long series. They’ve only been going back since 2004, so it’s not enough time to know for something as complicated and massive as the AMOC, what that really says. They use other data sets as well, none of which are great, but one of them is the water temperatures.

And that goes back to the 1850s for ridiculous reasons, having to do with curious voyagers on ships for the colonial powers and slave trade, and all of that horrible stuff. But anyway, they were also collecting water samples and writing it down in their log books. And so we have a very long record of what the temperature of the Atlantic should look like.

So by that, they’ve been seeing that it’s been deviating a lot from what it historically should be. So it appears that the current is slowing down and that it’s at the slowest it’s been in many decades, if not hundreds of years. So there are reasons to be worried that maybe it’s headed in a bad direction.

Separately, there’s also theoretical work that shows that the way that a system like the AMOC, which is driven by … This is going to get a little technical, but it’s driven by temperature gradients, and it’s driven by salinity gradients. So changes in salt content or temperature of neighboring bodies of water, basically, that when you have that kind of system, it can have two states, one where it flows naturally and normally, and one where it basically shuts off.

So the closer you get, you can basically switch very abruptly from the comfortable flow system to the basic shutoff system. It’s theoretical. We’ve seen it in climate models at this point, but we’ve never seen it in real life. So there’s a lot of questions around what exactly that would look like, but it seems pretty clear that those two states exist and that’s what they’re afraid of. They’re afraid that it’ll switch from healthy state to unhealthy state. And it’s not a clean line from one to the other where you can just back up. They are fundamentally different ways of operating.

Lauren Goode: There’s an alarming part of your story where you describe the potential breakdown of the climate that would happen from this AMOC shutdown. So this is a two part question. First part is two parts. One, I mean, when would this potentially happen? What are scientists saying about the timeline if this breakdown were to happen? And two, what are the effects of this?

Sandra Upson: So what the scientists are actually worried about is that we cross a tipping point, and that is the point where you cannot stop the Atlantic from sliding from that healthy operating state down to the no operation, shut down mode. They’re not actually worried that we’re going to immediately go to shutdown mode. Once you get to the tipping point though, you just can’t reverse it. It’s going to go under its own power to the other one. The classic example of a tipping point is you push a chair and it falls over.

Once you’ve pushed the chair, there’s basically nothing you can do to prevent it from falling over. And so the AMOC is like that in slow motion. So it would take decades up to a hundred years for it to truly shut off. But the effects would kick in pretty quickly. Like in the first five to 10 years, you would start to notice that temperatures in Europe would drop. You would start to notice that there’s more seasonality. So the winters are more intense. Summers are more intense overall, less rainfall in Europe, and it would just have pretty devastating effects over the decades on agriculture, in Europe in particular.

That’s where a lot of the research has been. However, what seems to actually be the bigger deal and where there hasn’t been a lot of very clear attempts to estimate what would actually happen is around the tropics with the ways that a shutdown of the AMOC would affect the rain bands that bring the monsoon seasons to huge swaths of population in Africa and India, Southeast Asia, and the effects that that would have of a pretty abrupt by human scales change to rain patterns. And then what do you do if the monsoon doesn’t come to India anymore? That’s just devastating, utterly devastating.

Lauren Goode: All right, we need to take a quick break, but when we come back, Sandra, we’re going to ask you what if anything can be done to change this.

[Break]

Lauren Goode: So, Sandra, we talk about climate change a lot at WIRED and sometimes on this podcast too, and what we can do about it. Get a heat pump. We had Matt Simon on a few weeks ago to talk about that, seems like a simple solution to energy efficiency at home, but the concerns about this mega current that circulates throughout the Atlantic just seems like the kind of thing that is just well beyond anything individual citizens can do to fix. It’s the ocean. So what do the climate scientists you spoke to say that we as a society, as tenants of planet Earth, are supposed to do about this?

Sandra Upson: Yeah. I mean, vote for politicians who will push for climate-aware policy. We need to transition way faster to renewable energy, electric vehicles. It’s a very familiar set of solutions. Susanna Ditlevsen, one of the scientists I talked to, I was a big proponent of degrowth.

Lauren Goode: What does that mean? I don’t think that that’s going to ever … Well, maybe we don’t always need to be on the up and to the right kind of graph always in this capitalist mindset. I think that might not go over so well in many parts of the US. It’s a very familiar answer. We’ve got to get a handle on our emissions, and it’s not one thing that any of us can really do on our own, except I guess I personally feel like our own actions have small, but perhaps tangible butterfly effects on others, on our commitment to trying to get better policies in our communities and our states countries. So try and live the life and make it happen on a bigger scale.

Michael Calore: Yeah.

Lauren Goode: This may be an oversimplified question, but can you draw a line between … Well, we reduce our carbon emissions and therefore this current does not reach the tipping point. What do our actions toward climate change actually do to change the way this current works?

Sandra Upson: That’s a great question, Lauren. One thing that is known quite well is that when you increase the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, a couple of things happen that have direct impact on the AMOC. One is that more rain starts to fall in the ocean near Greenland and Iceland, and that new water is fresh water. I didn’t really talk about the clear mechanisms of how the AMOC works, but the fresh water effectively slows down the AMOC’s ability to sink to the bottom.

It makes it harder for that water to fall. At the same time, Greenland has a lot of famous glaciers. Those glaciers are melting, and that meltwater flows into the ocean in that same exact spot near Greenland and Iceland. And that’s just a very sensitive place for the AMOC because that’s where all that overturning happens where it sinks to the bottom. And if it can’t sink, there’s kind of like no pump, there’s no engine. So if the AMOC stops being able to turn itself over, then it affects the rest of the circulation and everything slows down. But if we don’t put more CO2 in the air, then we don’t increase the rainfall. We don’t increase the glacial melt. So you can restore it in that way.

Michael Calore: One of the things that really struck me about the story that you wrote is that the paper that is the center of the story written by these sibling scientists in Denmark points to the possible collapse of the AMOC being about 25 or 30 years away. And that’s a shocking revelation because it’s an amount of time that is so close that it feels much more immediate because a lot of climate models, when they say, “Oh, there’s a disaster coming. There’s going to be catastrophic sea level rise in 150 years, in 200 years.” It’s very easy for people to put that out of their mind because it’s not going to happen to them. It’s not going to happen to anybody that they know or that they love.

But 25 years, 30 years, there are a lot of people that you know and a lot of people that you love who are going to be around in 25 or 30 years. And as you say in your story, it’s a date you can schedule, send an email to. It feels like the day after tomorrow. And that has a powerful emotional impact. And I’m wondering if that sort of impact … I mean, first of all, is that theory accepted? And if it is in the community, would that push people to act in a way that they wouldn’t if it felt further away?

Sandra Upson: Well, yes. First of all, you reminded me that I did actually schedule send an email to myself for 2057 just as fact-checking. I was just like, “Can I? Let me check.”

Michael Calore: What did the email say?

Sandra Upson: I was just looking it up. What did it say? Subject line is “The Future.” And then very cleverly, I wrote, “Can I send an email 30 years into the future?” That’s all I had to say to myself, 30 years from now.

Michael Calore: How’s the AMOC doing?

Sandra Upson: Both optimistic and dire. One would think letter to yourself that there’d be something a little more like, “Don’t forget, love is everything or whatever.” No, can I do this technical thing? Do people respond to the 30 years? Was that your question? I forgot your question. I was too interested in my email.

Michael Calore: Yeah, that was a question.

Sandra Upson: Yeah. I think that’s why it got a lot of attention. And then so they came up with this average date basically when they did a bunch of simulations of their model. There’s like, “Oh, 2057, this is the year. This is the year of tipping the point of no return.” But if you plot it looked at all of the model runs, it could tip next year, right? 2025 was the soonest it might tip and then it went out to 2095. So it could be anywhere in there.

But that immediacy of like, “Oh, it actually could potentially happen next year in their model was …” I think, I’m just terrifying. Like, “Wait, we don’t actually have unbounded amounts of time. This could happen anytime.” And maybe it’s an outlier risk. Maybe it’s not the biggest risk that we’re facing in terms of the likelihood, maybe the likelihood of an AMOC shutdown is not the highest thing ever, but the ramifications of it are so huge that you just don’t want to have that dice roll happen at all.

You just don’t want to see this happen. So I think people just realized that this is, I don’t know, actually within many of our lifetimes, knock on wood, and that’s a new kind of scary in the climate talk.

Lauren Goode: So this is the Day After Tomorrow movie that we’re talking about?

Sandra Upson: Yeah, except that the changes to the world and the climate happened over decades, not all at once. But the problem is that, there’s just so little information about what this current system is doing. We can’t even see it. There aren’t measurements of what’s happening to this water. So it’s very hard to get an accurate picture of what’s happening. And as a result, everything on some level is a guess. It’s an educated guess. And there are all these scientists that are arguing over what the right way to approach it is, what’s the best way to slice the data, what corrections should we be applying to it? What’s the best model?

Everyone has their own opinion, and it’s a big old mess. Lots of arguing on the science, but it also means that everyone is scrambling to make sense of a very dark, unclear picture. And as a result, almost anything is possible. It really is possible that it’s already tipped. And because we don’t have measurements, there’s no way to know. Chances are it hasn’t, but you can’t rule it out.

Lauren Goode: Well, on that slightly optimistic note, Sandra, thank you so much for joining us to share more about your story. It’s going to be on WIRED.com. By the time this podcast publishes, it’s also going to be in an upcoming print issue. But, Sandra, stick around because we want to hear your recommendation.

[Break]

Lauren Goode: Sandra, as our guest of honor, what is your recommendation this week?

Sandra Upson: My recommendation is for those people who are trying to learn a new language. So if you’re in that murky, intermediate phase where it just feels like there’s an infinite number of more things you need to learn, but you’re not stuck at the ground level, I highly recommend, what I found super enjoyable lately is watching very trashy reality shows in your language of choice. So the dumber the better. So dump a bunch of influencers on a deserted island or some awkward dating show or whatever. It’s just perfect because it’s very conversational, super casual, real youthful.

It’s how people actually talk. And because none of these people that they’re casting are like Einstein’s, the vocabulary is very basic. And it just takes something that you might consider kind of a guilty pleasure and strips that guilt right out of there. You get to be immersed in this very enjoyable, casual, real talk while watching people make just the worst choices about their lives. And it’s been super enjoyable for me, and maybe someone else would also benefit from trying this out.

Lauren Goode: I have so many questions. One is, are there really no scientists on Love Island or Survivor?

Michael Calore: They get filtered out by the producers.

Lauren Goode: If there are scientists, Einstein’s on these reality shows, we offer a blanket apology from WIRED. We’re sure you’re all very smart, but Sandra, what language are you watching these thrash reality shows in?

Sandra Upson: So I’ve been watching them in Dutch. I lived in the Netherlands when I was a small child and spoke Dutch, and I’m now trying to reconnect my roots, I suppose. So there’s one show in particular that’s actually an American dating reality series called FBoy Island that was also made in four different markets. And so one of them was in Dutch. And it was just a phenomenal linguistic experience. I learned among other things, just how many English words there are in very colloquial Dutch.

So for example, the word flabbergasted, it turns out is very popular in Dutch. They’d be going, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. I was so flabbergasted and I just loved that was the word. They decided to adopt among many others. But like flabbergasted, I guess, has a particular color that resonated well with the Dutchies.

Lauren Goode: That’s amazing. I recently went to Spain and I had taken Spanish throughout most of college, so I considered myself fairly conversant in it but no means fluent. But because I was going to Spain, I decided to brush up and I did Duolingo for over 30 days. I had a 39-day streak going. I was pretty excited about that. And then I went to Barcelona and was using my very rudimentary Spanish at the check-in desk at the hotel. And after a few minutes, the hotel concierge said very gently, most people speak Catalan here. So I got Spanish shamed.

Michael Calore: You got Catalan shamed?

Lauren Goode: I did. Which is OK. And then I mostly spoke English the rest of the time there.

Michael Calore: Smart.

Lauren Goode: Sandra, that’s a great recommendation. Thank you for that.

Sandra Upson: Anytime I got more where that came from.

Lauren Goode: We’re going to have to have you back on just for the recommendations. Forget the doomsday scenario, just come on. We’ll just do a whole episode of recommended. We do that at the end of the year, actually.

Michael Calore: Yeah, you’re the guest.

Lauren Goode: So maybe, Sandra, we’re booking you now. Mike, what’s your recommendation this week?

Michael Calore: Brat summer.

Lauren Goode: Yes.

Michael Calore: So I’m recommending this because, Lauren, I want you to explain to me what brat summer is. I’m a person who is really plugged into certain communities and not at all plugged into other communities. And I feel like I’m missing out on brat summer.

Lauren Goode: I’m going to do my best to explain it, but I have to be honest, I also had to have it explained to me, and we’re kind of like the Jake Tapper in this scenario. I don’t know if you saw that. He was on a news program the other day and someone had to explain it to him. So it comes from Charli XCS, the musical artist.

Michael Calore: Oh, OK.

Lauren Goode: XCX. Sorry.

Michael Calore: XCX.

Lauren Goode: OK. We already sound … I meant to say XCX, just to make that clear. I don’t know … Oh my God, this is really bad. I don’t know if it’s an album or a song. It might be neither.

Michael Calore: But it’s a piece of music by Charlie.

Lauren Goode: It’s called brat. And it references a person who is kind of messy, kind of sloppy kind of parties a lot, but cool.

Michael Calore: All right.

Lauren Goode: Yeah.

Michael Calore: Somebody I want to know.

Lauren Goode: That’s how I understand it. It’s a certain mojo. It’s like you’ve got the thing.

Michael Calore: So exhibiting those qualities would lead you to have a brat summer.

Lauren Goode: Has a positive connotation.

Michael Calore: Got it.

Lauren Goode: Similar to the way that hot girl summer had a moment and it’s like you got sort of zhuzh about you. But it’s funny that you’re recommending this, but you’re not wholly aware of what it is, but you’re embracing.

Michael Calore: Yeah, I’m embracing. I’m waiting for Cool Dad Summer.

Lauren Goode: Yeah. I mean, we can make that a thing.

Michael Calore: OK. Maybe next year.

Lauren Goode: I think cool dads are having their moment.

Michael Calore: Sure.

Lauren Goode: Yeah. Sure.

Michael Calore: Anyway, that’s my recommendation. Embrace the brat summer.

Lauren Goode: Embrace the brat summer. Are you drinking some coconut juice while you’re at it too?

Michael Calore: Fell out of a tree. Yes, I am.

Lauren Goode: OK, yes.

Michael Calore: All right.

Lauren Goode: What is your recommendation?

Michael Calore: I hope I was able to give you the proper context for that.

Lauren Goode: Oh no.

Michael Calore: Yes, I feel good. I feel good.

Lauren Goode: Good, good, good.

Michael Calore: What’s your recommendation?

Lauren Goode: My recommendation is a bit of an archive recommendation because in the several years that you and I have been doing this show, I’m pretty sure I’ve recommended it before, but it’s relevant to the chat we just had with Sandra. It’s a book called The Wave. It’s by Susan Casey. Susan is a journalist. She’s formerly the creative director of Outside Magazine. She has been editor in chief of O magazine, Oprah’s Magazine. She’s written three books, but two in particular I really like. One is called The Devil’s Teeth. That’s about the Farallon Islands and the shark population there.

And The Wave is, it’s mostly about this group of big wave surfers who she follows around. And in particular, Laird Hamilton, who was one of the pioneers of toe in surfing, which is relying on a jet ski to get you the right velocity that you need to surf really, really big waves. But the first part of the book, and once again, I’m recalling it from memory, having read it twice, but it’s been a while, is really this fascinating explainer of large waves, how they work, rogue waves, tsunamis.

It’s a good layman’s but scientific explanation of the movement of water and the formation of waves. I just totally nerd out on this book. I really like it. So if you’re interested in learning more about what Sandra has talked to us about today, first of all, go read her feature. Incredible. Second of all, maybe pick up the wave.

Michael Calore: Nice. That’s good.

Lauren Goode: All right. That’s our show for this week. Sandra, thank you again for joining us.

Sandra Upson: Thanks for having me. Thanks for listening to me jabber on about the Atlantic.

Lauren Goode: It was great. We were not at all flabbergasted. And thanks to all of you for listening. If you have feedback, you can find all of us on social media. Mike is on the fediverse.

Michael Calore: I am.

Lauren Goode: Find him there.

Michael Calore: Fully federated.

Lauren Goode: Just check the show notes. We’ll include all that information. Our producer is the excellent Boone Ashworth. We’ll be back next week and goodbye for now.

[Gadget Lab outro theme music plays]

Michael Calore: Do people really call them the Dutchies?

Sandra Upson: Yeah, including the Dutch. Yeah.

Michael Calore: Do they pass the Dutchies upon the left-hand side?

Sandra Upson: Yeah. Well, yes they do. On the bike lanes, if you’re going faster, you’re on the left-hand side. So yeah, you pass the Dutchies on the left-hand side.

Michael Calore: I think it’s just amazing, the Dutchies.

Sandra Upson: So cute, huh?

Michael Calore: That’s such a great little—

Lauren Goode: It’s really cute.